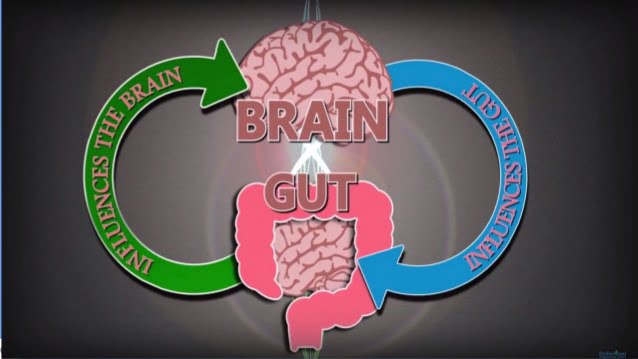

Scientists are busy proving that feeling you get in your gut when something isn’t quite right may be closer to fact than fiction!

Dr. Ai-Ling Lin from the University of Kentucky Sanders-Brown Center on Aging is investigating the ‘gut feeling’ that many people experience. These studies have shown that our guts and brains are even more closely connected than we believed. The two published studies demonstrate the effect of diet on the cognitive health in animals.

The first study which was published in Scientific Reports demonstrated that neurovascular function improved in mice  who followed a Ketogenic Diet regimen. “Neurovascular integrity, including cerebral blood flow and blood-brain barrier function, plays a major role in cognitive ability,” Lin said. “Recent science has suggested that neurovascular integrity might be regulated by the bacteria in the gut, so we set out to see whether the Ketogenic Diet enhanced brain vascular function and reduced neurodegeneration risk in young healthy mice.”

who followed a Ketogenic Diet regimen. “Neurovascular integrity, including cerebral blood flow and blood-brain barrier function, plays a major role in cognitive ability,” Lin said. “Recent science has suggested that neurovascular integrity might be regulated by the bacteria in the gut, so we set out to see whether the Ketogenic Diet enhanced brain vascular function and reduced neurodegeneration risk in young healthy mice.”

They considered that the Ketogenic Diet would make a good diet for the study because it utilizes high levels of fat and very low levels of carbohydrates. Another reason why the Ketogenic Diet made a good choice for the study is that it had previously shown positive results for the treatment of other neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, and autism.

Two different groups of mice were given either a regular diet or the Ketogenic Diet. After sixteen weeks the mice who had been following the Ketogenic Diet had increases in cerebral blood flow, lower blood glucose levels and body weight, improved balance in the microbiome in the gut, and an increase in the process which clears amyloid-beta fluid from the brain, which is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

“While diet modifications, the Ketogenic Diet, in particular, has demonstrated effectiveness in treating certain diseases, we chose to test healthy young mice using diet as a potential preventative measure,” Lin said. “We were delighted to see that we might indeed be able to use diet to mitigate risk for Alzheimer’s disease.”

“Our earlier work already demonstrated the positive effect rapamycin and caloric restriction had on neurovascular function,” Lin said. “We speculated that neuroimaging might allow us to see those changes in the living brain.”

The data from the second study suggested that caloric restriction could function as a fountain of youth for again mice, slowing down the aging process. Lin said so far, it’s too early to understand if the same diet regimes will transfer to humans, but there is hope.